Editor’s note: Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

The grave of a girl who lived more than 1,300 years ago in Great Britain continues to intrigue and baffle scientists and historians.

She was ceremoniously laid to rest with a gold and garnet-encrusted cross, and her burial site was uncovered more than a decade ago.

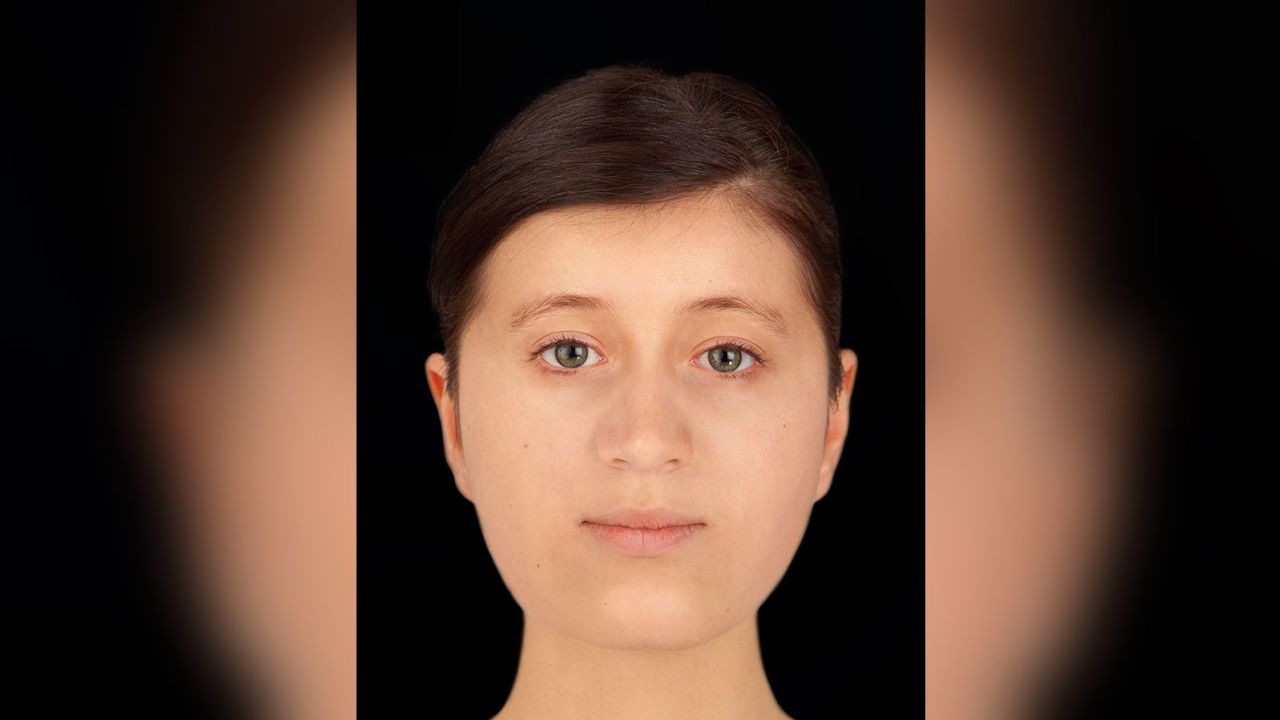

Now, researchers have reconstructed the face of this Anglo-Saxon girl — who was unearthed south of Cambridge near the English village of Trumpington in 2012 — as they continue to unlock her mysteries.

The remains of the teen, who died around the age of 16, according to researchers, presented striking questions: Where did she come from? Why was she given a bed burial, a custom typically associated with high-status women of the era? And how did she die?

“Personally, it’s really satisfying and strangely emotional to see the face of someone you’ve been studying for years, and to get to share their story,” said Dr. Sam Leggett, a bioarchaeologist at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, via email.

Uncovering the past

Leggett is part of a team that has been using modern technology to investigate the girl’s past. The research so far has revealed that she lived during the seventh century — between 600 and 700 — and likely traveled to England from the Alps in southern Germany. And her ornately decorated cross, often referred to as the Trumpington Cross, indicates she was likely an aristocrat, if not royalty, and one of the era’s earliest Christian converts.

“I hope the research we’re doing on Trumpington, and on similar burials in England will help to showcase the importance of women and girls in the early medieval world, the Christian Church in particular, and the power and importance they held in society in the 7th century,” Leggett said.

Leggett and her fellow bioarchaeologists were able to use isotopic analysis — which involves studying bones on the atomic level — to uncover details about the girl’s diet and health. The analysis showed she may have experienced a dramatic change after arriving in what’s now the United Kingdom, with less access to protein. She likely suffered from illness, the research revealed.

There is, however, still much to learn about her life. DNA analysis has not been carried out, though that work is ongoing, according to Leggett. Such DNA sequencing remains expensive, but it could uncover a host of other details about the girl.

Recreating her face

Forensic artist Hew Morrison created the girl’s facial reconstruction. But without the DNA results, her hair and eye color remained a matter of guesswork, Morrison told CNN by email. He said he was able to use data on facial tissue depth to imagine her features.

“(T)here is more room for artistic license when it is a facial reconstruction of a historical person, as opposed to a live forensic case,” Morrison noted.

Still, the reconstruction offers a new way for the public to imagine the girl as a living person, rather than an academic enigma.

“It’s not necessarily an analytical step,” said Dr. Sam Lucy, an archaeologist at the University of Cambridge involved in research on the girl and an expert on the time period in which she lived.

“The main point of doing it is to humanize her,” Lucy said, referring to the facial reconstruction. “It helps you to remember that these were people who had hopes and dreams, and died young, and had episodes of ill health — and were probably quite a special person, but perhaps also quite an ill person.”

Lucy said she’s still hoping to figure out why the girl was buried near Cambridge and what significance the area may have held for people of that time.

The field where the remains were found “was probably part of a settlement,” Lucy said.

But what intrigues the archaeologist most about that period of time — and the burial site — is what scientists still don’t know about the seventh century.

“It’s that period where we think it’s a historical period, but actually, we don’t really have much in the way of historical documentation for it,” Lucy said by phone. “So people think they understand it, but when you go back and look at what texts there are, it’s by no means a full picture.”

The girl’s likeness as well as her ornate cross is on display at the University of Cambridge’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in an exhibition called “Beneath Our Feet: Archaeology of the Cambridge Region,” which opened Wednesday and runs through April 14, according to a news release.