Editor’s Note: Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

During their quest to find the source of one of the brightest and most powerful explosions in the universe, astronomers discovered a new chaotic way that stars can die.

The bright flash of gamma-ray light was first detected by NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory on October 19, 2019. The explosion lasted just over a minute — considered long, like any gamma-ray burst, or GRB, that lasts more than two seconds.

Most GRBs have been traced back to the collapse of stars with at least 10 times the mass of our sun or to the mergers between neutron stars — the dense remnants left behind when large stars explode.

But the October 2019 burst, named GRB 191019A, came from a different source, revealing a type of stellar death that had been theorized but never observed.

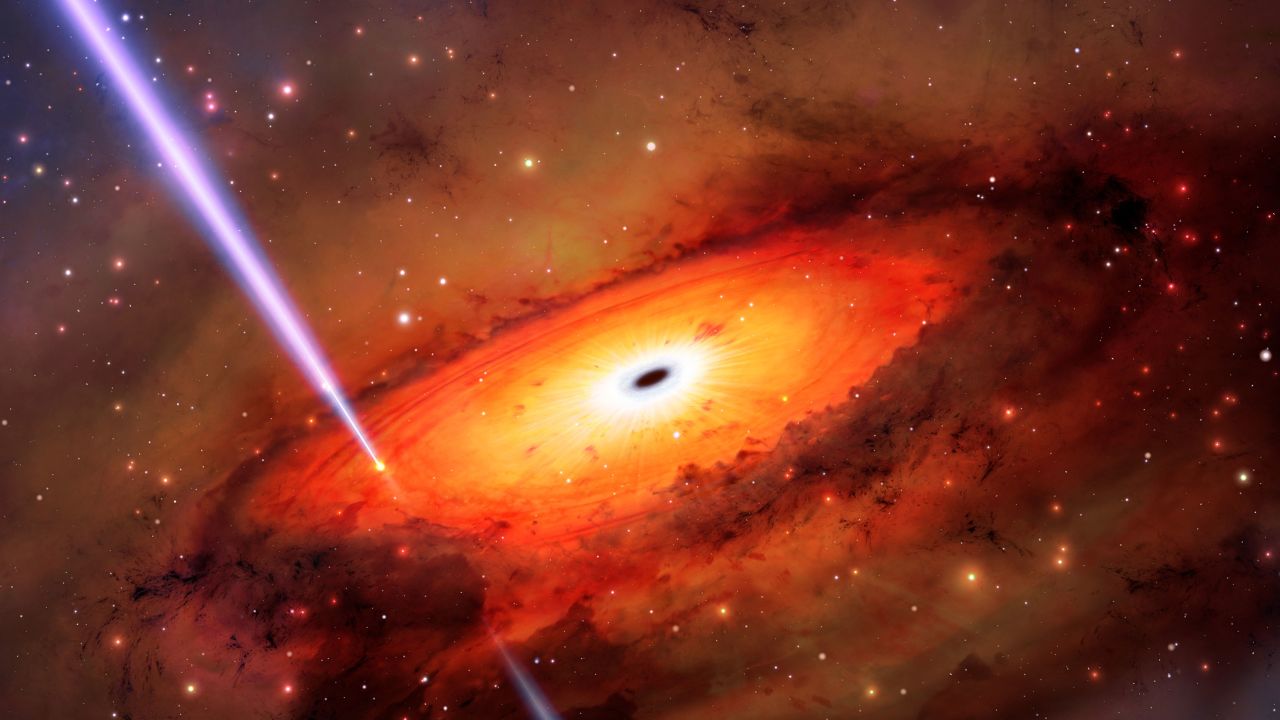

Astronomers believe the burst occurred when stars, or possibly the remnants of stars, collided within the densely crowded environment near the supermassive black hole at the center of an ancient galaxy. A study detailing the findings published Thursday in the journal Nature Astronomy.

“For every hundred events that fit into the traditional classification scheme of gamma-ray bursts, there is at least one oddball that throws us for a loop,” said study coauthor Wen-fai Fong, assistant professor of physics and astronomy at Northwestern University’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, in a statement. “However, it is these oddballs that tell us the most about the spectacular diversity of explosions that the universe is capable of.”

How stars die

Over time, astronomers have observed what they categorize as the three main ways that stars can die, depending on their mass. Lower mass stars like our sun shed their outer layers as they age, eventually becoming dead white dwarf stars.

Massive stars burn through the fuel-like elements at their core and shatter in explosions called supernovas. These violent, destructive bursts can leave behind dense remnants like neutron stars or result in the creation of black holes.

A third form of star death results when neutron stars or black holes begin to orbit one another in a binary system and spiral closer to one another until they collide and explode. But astronomers may need to add a fourth scenario to the list.

“Our results show that stars can meet their demise in some of the densest regions of the universe, where they can be driven to collide,” said lead study author Andrew Levan, an astrophysics professor at Radboud University in Nijmegen, Netherlands, in a statement. “This is exciting for understanding how stars die and for answering other questions, such as what unexpected sources might create gravitational waves that we could detect on Earth.”

Gravitational waves, or ripples in space-time first predicted by Albert Einstein and initially detected in 2016, can occur when neutron stars or black holes collide.

Why ancient galaxies could hide star deaths

During their search for the origin of the gamma-ray burst, astronomers used the Gemini South telescope located in Chile to observe the afterglow of the cosmic explosion. Their observations pointed to a location less than 100 light-years from the core of an ancient galaxy.

But the telltale signs of a supernova were missing.

“The lack of a supernova accompanying the long GRB 191019A tells us that this burst is not a typical massive star collapse,” said study coauthor Jillian Rastinejad, a doctoral student of astronomy at Northwestern, in a statement. “The location of GRB 191019A, embedded in the nucleus of the host galaxy, teases a predicted but not yet evidenced theory for how gravitational-wave emitting sources might form.”

Ancient galaxies, which can be billions of years old, aren’t hubs of active star formation. But at their core, these older galaxies are filled with stars and remnants like white dwarfs, black holes and neutron stars. Compared with younger, more typical galaxies, ancient galaxies can have up to a million or more stars densely packed into their cores.

Astronomers thought it likely that stellar collisions could occur in these dense regions, especially so near to the strong gravitational pull of a supermassive black hole at the galactic center. The researchers liken it to a demolition derby, where the black hole’s gravitational influence can send stars zooming in different directions, eventually colliding in cataclysmic explosions.

But they had no evidence for any long gamma-ray bursts originating from ancient galaxies — until now.

If the chaotic environments at the center of ancient galaxies can result in stellar collisions that release bright, powerful gamma rays, why haven’t astronomers seen them before?

The researchers believe that the centers of such old galaxies are cloaked in vast amounts of gas and dust, which could obscure the gamma-ray burst. That would mean the 2019 event was an exception.

“While this event is the first of its kind to be discovered, it’s possible there are more out there that are hidden by the large amounts of dust close to their galaxies,” said Fong, who is also a member of the Center for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics at Northwestern. “Indeed, if this long-duration event came from merging compact objects, it contributes to the growing population of GRBs that defies our traditional classifications.”